I write to you via my iPhone on the second floor of a double-decker bus, knees jammed against the seat in front of me, 19 hours deep into a 32-hour journey to Iguazú Falls— one of the 7 natural wonders of the world. For the last four hours, we’ve been rattling down a dirt road, past thousands of cows, entering Misiones, where the landscape has begun to shift to towering yerba mate trees. This region grows 75% of the world’s mate.

We were told it’d be a 26-hour ride, but apparently roadside asados are a non-negotiable detour, as we’ve stopped twice to slow-grill a cow.

The bus driver is blasting Cumbia music through the crusty intercom as I experience a chronic muscle spasm in the hip flexor region. My travel companion is Santi, a tennis buddy and newly minted dentist. Thanks to Argentina’s free healthcare, he’s been deep-cleaning my teeth and plans to fix my chipped incisor. The only English phrase he knows (and repeats often) is “the life is one,” a charmingly butchered translation of solo hay una vida—the Spanish equivalent of YOLO.

Santi and I are the youngest passengers by about three decades, and when word spread that a gringo was onboard, I was surrounded by seniors and peppered with questions about the new Papa Yankee (American pope) and whether I believe in god.

The most common word spoken in Argentina is Boludo, which roughly translates to buffoon, and plays a central role in Argentine culture. It’s used as a filler word, an insult, a term of endearment, and a verb. This buffoonery is a sacred part of Argentine culture, and is omnipresent across class and age. It’s not just that tomfoolery is normal here; it’s considered essential. “Nacimos y morimos boludos,” one elderly woman told me—we’re born and die as boludos. Nobody takes themselves too seriously. Famously, there’s no direct translation for “awkward” in Spanish, and Argentines make a point of preserving the sense of “play” that we often leave behind in the etiquette of adulthood.

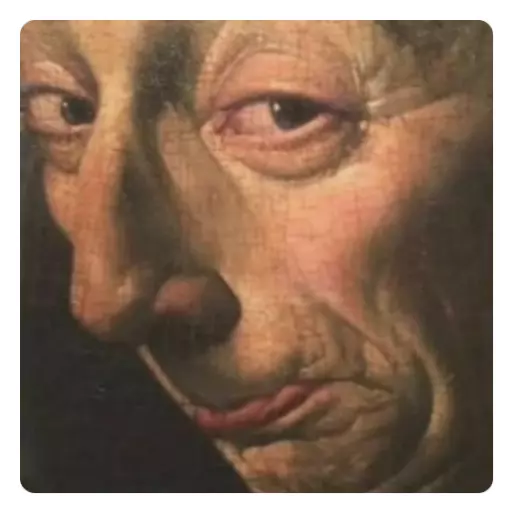

For example, when Boca Juniors scored a goal against Bayern, I saw this bona fide boludo scoop up a beefy stray pit-bull off the street and drop a fat smooch on his lips in a moment of visceral jubilation.

In other news, after a friend diagnosed me with chronic issues in my hip gyration capabilities, he’s offered to give me some pro bono dance classes. Across all Argentine music, dancing is no upper-body, all hips—cuarteto is partner dancing and bouncy gyrations, cumbia is side-to-side booty rolls, folklore is swaying and stomping, and reggaetón is all-out pelvic warfare. I’m a baby giraffe with every style, but if it’s any consolation, I have gotten some cookie points for my pasión on the dance floor. “You dance with your hands,” my friend said. “I’ve never seen anybody move their body like that in my entire life.”

I’m also conquering my fear of raw meat. In San Luis, the equivalent of New York’s corner deli is the carnicería— the butcher shop. They’re perched on every corner. When I ask for a cut, the butcher saws it off a hanging carcass. It’s a genuine farm-to-table experience.

Last weekend, San Luis was buzzing with a parade in the plaza as news had broken that the national asado championship had just been won—for the first time ever—by a woman from San Luis!

I’ve greatly enjoyed organizing games and activities for my English conversation club attendees, which is open to all members and ages in the greater San Luis community—I’ve been getting routinely dominated by an 8-year-old in Sushi-Go.

One woman in her 70s takes an hour-long bus to come to my conversation club, and sends me morning inspiration messages at 8am each time:

My Spanish is certainly improving, but I still find that I say what I can, not what I want to. My Spanish-speaking personality is curt, my words simple and prosaic. “It seems like you are thinking very hard when you speak,” one friend noted.

Luckily, Argentines communicate primarily in stickers — here are a few of my favorite:

A few weeks ago, I visited a nearby town and was mounted upon the back of a horse by a guy who spoke highly unintelligible Spanish; suddenly we were cantering along the side of the highway, summiting steep sierras, and crossing rushing rivers. Stray dogs nibbled at the heels of my stallion, and I was profoundly pressed that she would buck me into oblivion.

The novelty of being here has mostly worn off, and the intensity of living all on my own for the last few months has taken a toll. I’ve been trying to find grace in the solo routine, though it’s come with some alarming side effects— Bellowing gospel music in the shower, scrambling morning eggs in the nude, and allowing my laundry to pile to heinous heights before spending an afternoon scrubbing away on the patio.

I’ve been trying to find inspiration in absence, in the negative space solitude creates. I do feel like the solo time has allowed me to observe the world at more of a distance, taking account of tiny truths that would normally pass me by, and I’ve been working on a little film that stitches together these kernels of life. And yet, the longer I go alone, the more I understand: there’s no substitute for being near other warm, breathing things.

I was feeling especially gloomy on Father’s Day, after a few weeks of almost entirely solo time, until I got invited to a friend’s Father’s Day dinner. I decided to pull myself out of the rut and attend, and ended up in the middle of a full-blown quilombo—an Argentine term for people-induced ruckus.

My selfie stick arm was employed, the seniors were thunderstruck by my towering height, and now I’m being pulled into early contract negotiations for various arranged marriages here.

The abuelo took a liking to me and ran the asado while unspooling a mantra-infused monologue about his life. He had his first kid at 17, four by my age, and now his family gatherings are over 50 people strong. He pulled me close and whispered in my ear: “Family is like growing a tree. You start with the roots, the leaves, the branches, and now, running around me are the fruit. My grandchildren! This is my faith,” he said. “My faith is in family.”

After 32 painful hours, our squadron of senior citizens and the lanky gringo stumbled off the bus and straight onto a boat that took us directly underneath the Iguazú Falls, which sits at the crossroads of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay. There were audible gasps as the boat driver told us that next month, Iguazú Park will be closed because Messi is coming to visit for the first time.

After a delirium of two days on the bus, being face to face with the falls was quite literally a slap to the senses.

Iguazú Falls was formed by volcanic eruptions over 100 million years ago. But the Guaraní people tell a more compelling story: Naipí, a beautiful Guaraní woman, was chosen to be sacrificed to the serpent god Mboí. But she fled with her lover, the warrior Tarobá, in a canoe down the Iguazú River. Enraged, Mboí split the river in two, creating the great falls and swallowing them in the cascade. He turned Naipí into a rock at the base of the falls and Tarobá into a palm tree at the top before descending into La Garganta del Diablo, The Devil’s Throat.

Even today, when the mist rises and the rainbows arc across the falls, people say you can see their spirits reaching for one another, always close, but never able to touch.

How could you encounter such a natural behemoth and not believe in its fables? We stood before La Garganta del Diablo, the largest of the 275 waterfalls of Iguazú. I stood in a hypnotic trance at the edge of the ancient, vast, unrelenting wall of water. 1.5 million litres of water falling every second, tumbling into the devil’s throat. We are so, so, so small, I thought.

The pitbull kiss is so tender 😭

You had me at the max hofs replacement